Evidence Tips for Prosecutors:

Technology Abuse

In today’s digital age, prosecutors need to know how to prosecute cases that include technology-related evidence. This resource will give tips on how to more effectively prepare a case that involves the misuse of technology.

Technology can provide evidence where it might not have existed before; capturing important communications and offender actions. Though technology may initially appear intimidating, the rules of evidence are generally sufficient to include evidence from new technologies. For example, the process to admit a handwritten note is fundamentally the same method used to admit text messages from a digital device. In many cases, admitting tech evidence is very similar to the process of admitting more traditional forms of physical evidence.

Please note that this tip sheet is not intended to be legal advice.

This guide is a part of a series that provides tips and considerations for collecting evidence related to the misuse of technology in cases involving domestic and sexual violence or stalking. Other topics in the series include collecting evidence related to emails, telephone calls, social media, online images and videos, spyware, electronic surveillance, and location tracking.

Before proceeding, please make sure to read the Primer for Using the Legal Systems Toolkit. It contains information that is essential to understanding all of the documents within this toolkit.

Who should use this resource?

This resource was created specifically for use by law enforcement and prosecutors. While survivors and other allied professionals may find the information useful, it’s important to know that the recommendations are specifically geared toward those working within legal systems.

IMPORTANT TIP FOR ADVOCATES: If you are a non-attorney victim advocate, it is strongly recommended that you do NOT collect or store evidence for clients. While helping clients to gather evidence can be of great assistance, it is important that you give the survivor the skills to gather the evidence rather than gathering it or storing it yourself. Gathering or storing evidence can impact the chain of custody and can lead to you being forced to testify about the collected or stored evidence. Testifying in court can undermine confidentiality protections, and negatively impact both your client and the integrity of your program. If you have questions, please contact Safety Net.

Pretrial Considerations

Empower Survivors

While investigators often have specialized expertise in unearthing evidence, it is important to remember that survivors have a great deal of knowledge about their own experience and can be essential to locating useful evidence. Seek out assistance from the survivor whenever possible, identifying what types of evidence you are looking for and specifically letting them know what you plan to do with the evidence. Make sure to let the survivor know whether they will be able to object to the use of certain evidence that is uncovered and what requirements you may have to turn over evidence, including embarrassing content. Trust is essential to locating evidence and to ensuring victim participation.

Build an Evidentiary List

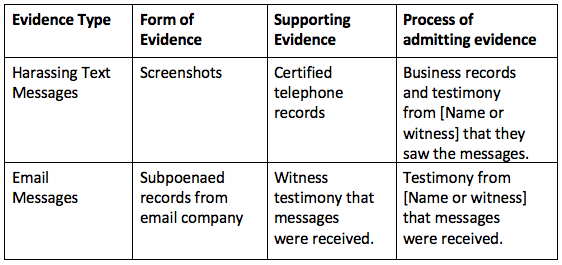

Organization is essential to presenting a successful and seamless case. Make a list of all the evidence that you plan to introduce (technology and non-technology-related). Next, determine the form in which you intend to enter this evidence and write this next to the evidentiary item. For example, if you are trying to admit text messages, determine whether you will introduce printed screenshots, a forensic analysis of a mobile device by police investigators, testimony by a witness, or some combination of evidence. Make note of whether there is any supporting evidence and what process you will use to try and admit the evidence. At times, the process for the primary and supporting evidence may be the same, for example, a witness or business records may be used for both types of evidence. If a witness will be used, write down the witnesses’ name next to each item you will be introducing. Authentication is a critical component of admitting evidence. You should identify how you plan to authenticate each piece of evidence. Here is an example of a table that might be helpful.

Authenticating Evidence

Authentication is the process of proving that a piece of evidence is more likely than not what you claim it to be. The federal rule of authenticity can be found in FRE 901.[1] You do not need to prove authenticity beyond a reasonable doubt. However, while the standard for authenticity is low, you still have the burden of proving to a court or jury that the evidence helps to prove your case. To do that, you will need to show that the evidence is what you say it is and that the evidence is attributable to the source that you say created it. When authenticating evidence there are two steps you will need to follow:

Step 1: Show that the item is what you claim it to be. This is where the list you made during pretrial prep comes in handy. For instance, if you are seeking to introduce a text message you will have your witness testify that they received the message on X date and at Y time and from a number associated with the offender.

Step 2: Tie the evidence back to the offender. A text message is a perfect example of how challenging it can be to tie digital evidence to an offender. To link a text message, you must show that the message was sent from a device that the offender had access to, and also that it was the offender who authored the message. It is not enough to show the message came from the offender’s email address or cell phone number. Authentication of messaging evidence requires proof of authorship. Proof that a person had exclusive access to a device during the relevant time period is often sufficient and is regularly proven through circumstantial evidence.

Technology evidence can often be linked to the offender through a digital trail, including an IP (Internet Protocol) address, digital forensics, or business records from technology companies. Frequently, technology evidence is authenticated through testimony, including from a victim or law enforcement. However, proving that an offender authored a message may require circumstantial evidence. For instance, certain words or content used in the message or the way a message is written can help to prove that only the offender would have authored it.

*Note: Each piece of evidence you are admitting will need to be individually authenticated. For example, do not assume that because one text message is authenticated that the rest of the chain is also authenticated.

Don’t Fear Motions in Limine

Opposing attorneys may seek to limit your ability to present evidence by filing a pretrial motion in limine.[2] While pretrial motions can be challenging, these challenges have the benefit of providing a sense of whether the court is knowledgeable about your type of evidence. If the court is not familiar with the evidence, you have the opportunity to educate the judge prior to trial. Additionally, pretrial motions allow you to present key points of your case and to get a sense of how the court may rule. Lastly, the court’s ruling may help you correct any deficiencies or problems in your case. Lastly, getting advanced rulings on your evidence helps to ensure that you do not have to argue about your evidence in front of the jury and that you will not have to unexpectedly proceed without a key piece of evidence.

Anticipate and Prepare for Objections

Even after pretrial motions have been decided, it is important to be prepared for possible objections. Anticipating objections will help you to keep your composure, prepare your response, and keep the jury focused on your case and not the issue opposing counsel is raising. For every piece of evidence, be prepared to argue why an objection should be overruled. Below is a list of common objections, though it is a good idea to familiarize yourself with your jurisdiction’s rules in order to protect against uncommon objections as well.

Hearsay (FRE 801(c))

Hearsay Exceptions (FRE 803)

Relevance (FRE 401)

Unfair Prejudice (FRE 403)

Best Evidence Rule (FRE 1001-1002)

Best Evidence Rule Exceptions (FRE 1003)

Lack of authentication (FRE 901)

Prepare the Victim

Confronting the abuser in court can be extremely difficult for a survivor of domestic or sexual violence. Preparing the survivor on what to expect during the course of the trial will go a long way in easing the anxiety and trepidation they may be experiencing. The survivor’s testimony is often times the best piece of evidence. Therefore, preparing this testimony is just as important as preparing all the other parts of your case prior to trial.

When you meet with the survivor you will want to describe what they can expect during the trial itself. Explain what the courtroom will look like, where people will be seated, and what to expect during the proceeding. Make sure that the witness has all of their documentation in order so that if their memory needs to be refreshed while testifying you have that on hand. Depending on the level of trauma experienced it is possible the survivor will not recall precise dates and times, particularly in a chronological order.

Other items you will want to discuss prior to the trial date include where the court house is located, where parking is available, and if cell phones are allowed in the courtroom. It’s easy to forget that people may not know these details. It’s also critical to help survivors to identify any possible threats to their safety. For instance, does the witness need to be escorted to the courtroom? Should the witness park in a different location so the offender does not have access to the car? These are all important considerations when working with survivors. Finally, have these discussions well in advance of the trial date so there is time for the survivor to process the information and for you to make necessary safety arrangements.

Trial

Completing the above processes will help to make your case more successful. However, during all aspects of the trial including the proceeding and recesses, you should pay attention to any behavior by the offender or others which aims to intimidate, threaten, or frighten the survivor. These behaviors may be discreet or only have a meaning that is understood by the survivor. Frequently, offenders will send text messages or have other people call the survivor around the time of the trial. It is important to ask about any inappropriate communication and to report any of this behavior immediately to the judge and opposing counsel.

Sentencing

Be prepared to argue all of the facts, including those not allowed into the trial, in order to receive your requested sentence. This might include any danger or threat assessments that were conducted pre-trial, the defendant’s past history including any violations (this will usually be done through a pre-sentence report), or the type of technology misused by the defendant.

Sentencing can be an extremely powerful opportunity for a survivor to speak freely about their experience. The victim impact statement can be persuasive, impactful, and cathartic. Consider what special conditions of supervision you will want for this particular defendant, including if there are any technology-related provisions. At this point in the case, you should be intimately aware of the types of technologies misused by the offender. Argue for special conditions or prohibitions that will address technology misuse. Finally, do not forget to argue for any restitution owed to the victim. There is usually a monetary cap for the amount that can be ordered by the court and so also consider referring the survivor to other sources of relief such as the Crime Victims Fund.

[1] State evidence rule may vary, but many states mirror the federal rules. Check your state’s rules to ensure compliance with local and state evidence guidelines, including the court rules, which may have specific requirements about how to present evidence.

[2] Motions in limine are usually filed to preclude evidence from trial. In some jurisdictions, the party seeking to introduce evidence may also file a motion in limine to seek a ruling from the court about the admissibility of their own evidence.